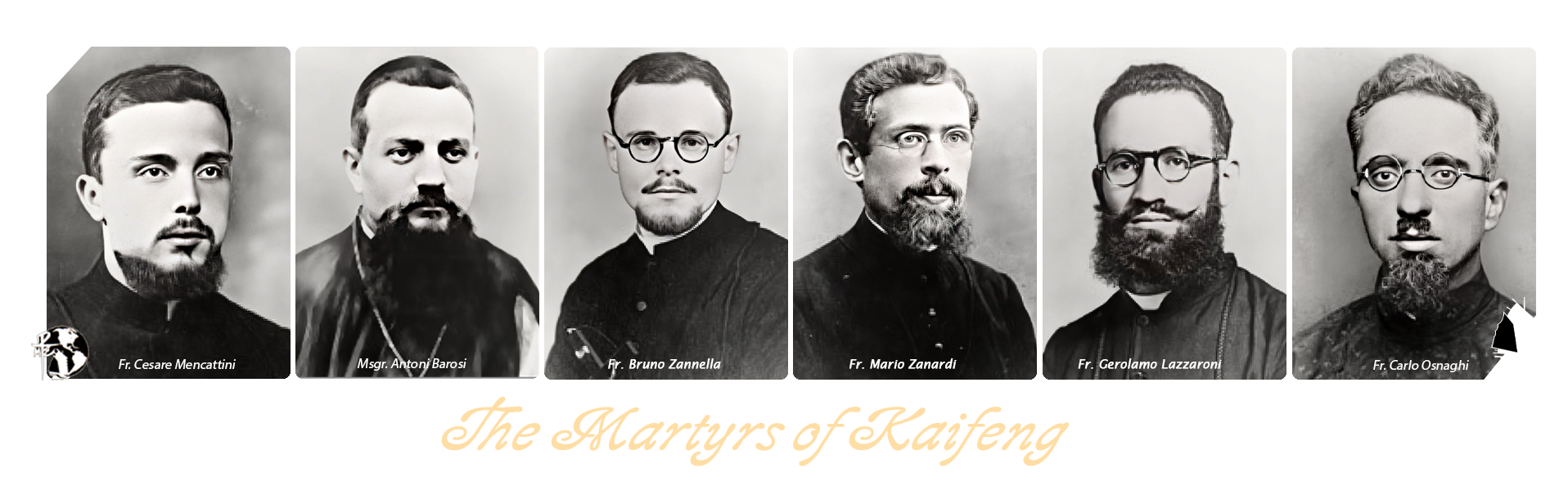

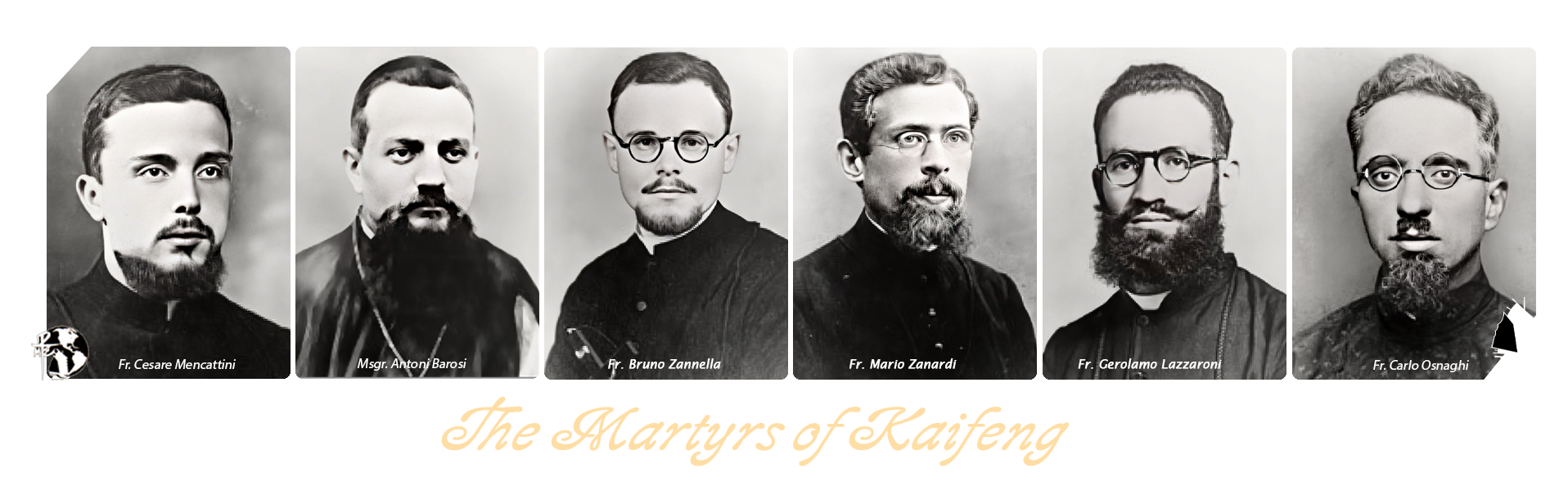

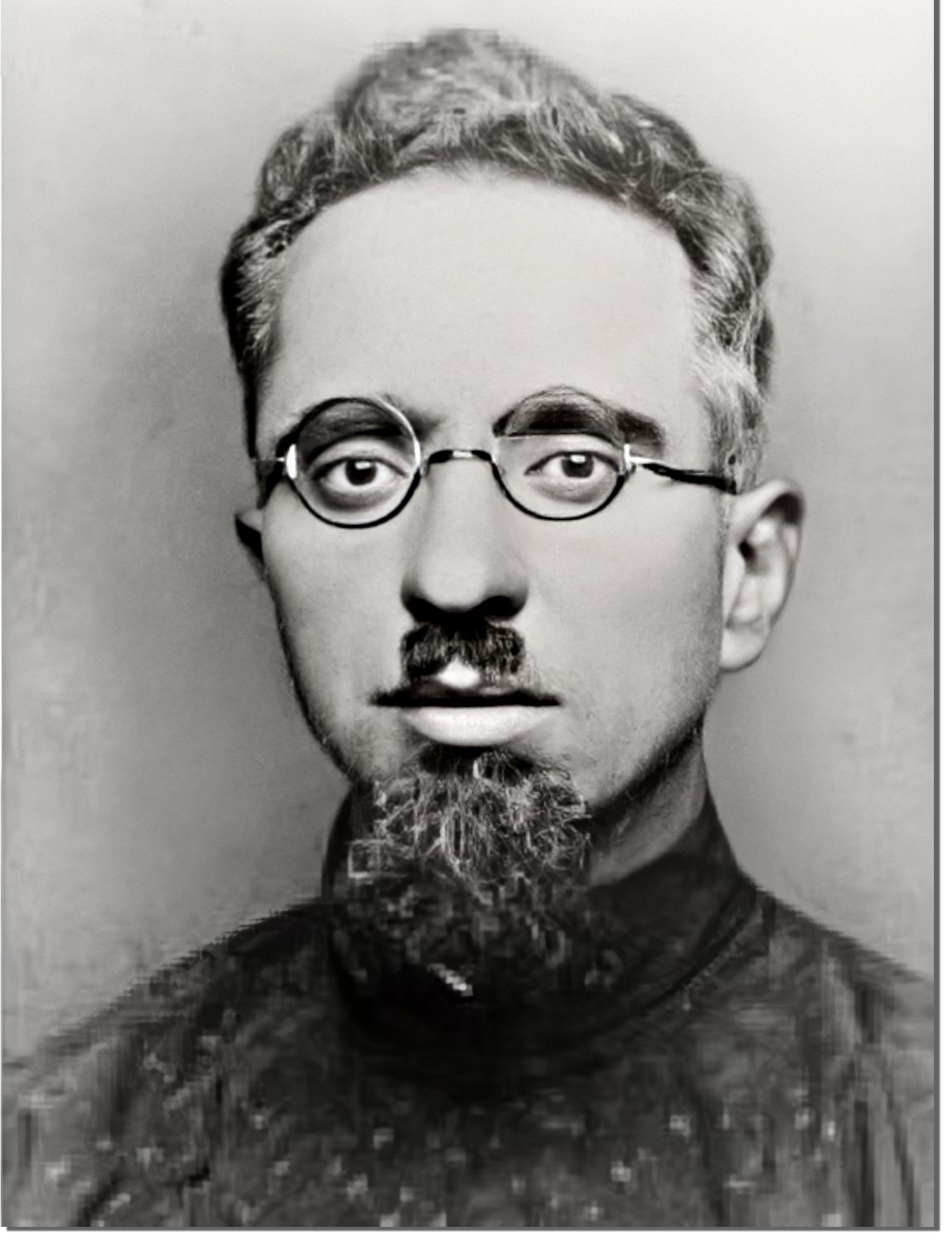

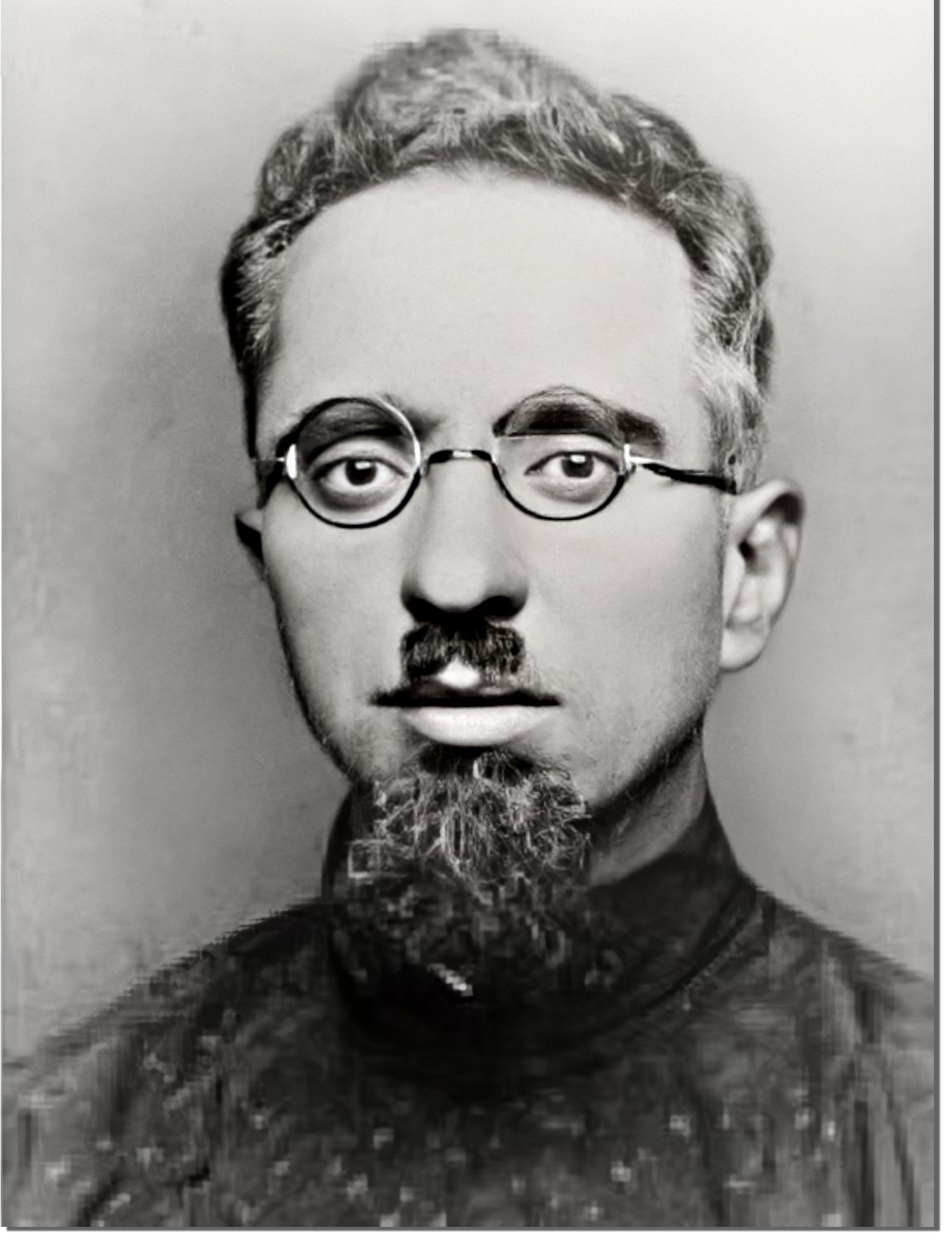

Father Carlo Osnaghi

(October 26, 1899 - February 2, 1942)

The sun has long since set on this faraway prairie of Yejigang. It's very cold on the night of February 1, 1942, with drizzling rain driven by a strong north wind. Fr. Carlo Osnaghi stirs restlessly on his cot.

He has suffered insomnia since his youth, and even in the mission he has spent many a sleepless night. The nighttime hours are long, but also very "fruitful" especially for one who slips easily into memories. Fr. Carlo remembers the nights spent bent over tattered notebooks, correcting Latin translations and math problems. That was in 1924 when, as soon as he arrived in Kaifeng, the bishop assigned him to teach in the seminary. He had never imagined, during his own years of formation, that his missionary life would consist of spending time with Cicero and the Pythagorean theorem.

Now, however, he has something different to keep him awake. Indeed, it is not a night spent in study nor the preparation of-classes, and his worry has nothing to do with the undisciplined students who laugh irreverently when he, the professor, mangles a monosyllabic Chinese word, changing its meaning completely.

No, it is the voices coming from the other corner of the hut that give him no peace. Loud and angry voices, fortified by who knows how many glasses of rice wine, voices suggesting greater violence to come. They curse him, the bishop, and all the priests who have so little consideration for his life that they will not pay the ransom demand. He tries not to think about it. He nudges the Chinese catechist, his unlucky companion, who continually stares at him with wide eyes. He can't sleep either. He knows very well that at any moment their captors could decide their fate. Only Huang San, the 12-year-old boy lying nearby, seems blessed with sleep. Why should he worry? Surely he knows that his father, the eminent mandarin of the area, will do something to come and save him or will pay the last cent required for his release. Fr. Carlo, on the other hand, knows that it is much different for him. He is sure that his superiors are doing everything they can to free him from this prison and that negotiations have gone on for several days; but he is just as sure that there is no way his confreres can come up with the 500,000 dollars required to pay for his release.

The anxiety grows and grows. Once again he turns to look at his catechist. He is filled with admiration for this simple and courageous Christian who insisted on following and staying with him, even when he~ was given the chance to leave freely.

The brigands holding them hostage begin to argue. Fr. Carlo hears his name among the shouts. His nervousness increases. He looks through the pockets of his pajamas, the same ones he was wearing when he was taken away in the middle of the night. He finds his rosary and anxiously begins to pray the Hail Mary. His tired eyes look out into emptiness.

Even though he has been held captive for twenty days, he still cannot believe that this is happening to him. In his mind, he still hears those insistent knocks on the door of his mission house in Yejigang.

It was the night of January 12 when, jumping out of bed, he rushed to the door to see who was in such urgent need. For a moment he thought that it had to do with a request for last rites. But as soon as he found his glasses and his sight became accustomed to the dark of the night, he knew that this wasn't the case. A large group of armed men immediately grabbed him and tied him up.

Then they were in the house, tearing it apart. They turned the church upside down as well, stealing anything they could. Then the missionary, the catechist and the young boy were brought to a hut in an open field on the northeast border of Henan, so that at the slightest hint of danger the band would be able to escape easily into another province.

Fr. Carlo, still dazed, and unbelieving, let himself be dragged away without any resistance.

Often during his eighteen years in China he had thought about, and even desired, a violent death like that of Jesus, for the sake of the Gospel. And this thought amazed him, not so much because it was out of place, but because it was so out of character with his general timidity. How could he, who was "afraid of his own shadow," find the courage necessary for martyrdom? But with the passage of time, he learned to live with these feelings and to allow his hidden determination to emerge. He knew well that he was no hero, and in fact heroism never seemed important to him. It was enough for him to be a good missionary, and that's all. And so he discovered the silent martyrdom which daily accompanies that acceptance of one's own fragility.

Meanwhile the rosary flows quickly through his fingers. He has always had a great fear of the brigands. His bishop knew this, and in 1926, after only a few months in the district of Yuanzhai, which was teeming with armed bands, he called Fr. Osnaghi back to Kaifeng and appointed him as assistant pastor at the Cathedral and chaplain of the orphanage.

But this time there is no "emergency exit." He cannot think about what might have been, but must face the reality before him. And the brigands engaged in heated debate are that reality now. He is in their hands. His thoughts go to his confreres who have just been killed in Dingcunji.

A shiver runs through his body. He thinks back upon those tragic events, how the news reached Kaifeng at the beginning of the year that his four confreres had been murdered. He had known Fr. Zanella especially well, because he had worked in Yeijigang; in fact, in 1937, he was the one Fr. Osnaghi was sent to replace.

What a shock to hear that story! Fr. Carlo could not help but reveal his feelings to his mother, to whom he was quite attached:

"We are all at a loss. It almost seems like a dream. Let us pray that the blood of these victims will be the last. From heaven may they look down upon all of us who remain in this troubled land, so full of thorns, and protect us. But if it must be, may they give us the strength to die as generously as they did."

His mother - while he continues to pray, her image becomes more and more clear to him. He has written to her often, confiding in her every joy, difficulty, and worry. In 1930, after various experiences in Kaifeng, he was sent to Fengjiao, the center of three ancient Christian villages, not far from the city of Luyi. With his mother he rejoiced about his Christian communities and spoke to her about his pastoral work. He shared his dreams with her. He liked it there a lot and could have stayed there forever. Instead, in November of 1937, he was transferred to the district of Yejigang, once a flourishing market, when the Yellow River flowed near. It had been aptly called "Pheasant Hill," even though now not a single pheasant was to be found, only poverty and squalor, caused by the river's change of course.

These were difficult times for Fr. Carlo. His memory goes to the numerous villages in the different communities, the long trips he had to made on foot, since his bad eyesight would not allow him to go by bicycle, to the nights spent in seedy inns or among the poor Christians. And then, upon his return to the mission house, there was always some surprise, like the time he found it completely looted by thieves.

But these physical problems were not the only ones. Because of the intensification of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937, Fr. Carlo was increasingly seen as a dangerous enemy, just for the fact that he was a foreigner. Any kind of hospitality began to disappear, to be replaced by suspicion and fear on the part of anyone he met. Yet, he never stopped loving these people: "Poor, unhappy China! How much we, your latest apostles, love you; we're ready to undergo anything to save you from the abyss. And if God desires victims of expiation, here we are!" His mind returns to that period of time when he found it difficult to see and feel the presence of God, as he confided to his mother: "To make matters worse, sometimes God seems to be hidden, and I come into His presence like a piece of wood, without any fervor at all. This is to suffer a slow martyrdom of the soul. But I accept any trial, if only I might have the grace to truly love God."

While the strong wind continues to blow through the walls of the hut, his prayers become more subdued. No voices are heard now. Maybe everyone is asleep. Even the catechist is drowsy. The first light of dawn slowly advances through the whirlwind of fine sand whipped up by the wind along the Yellow River.

It is February 2, 1942. The brigands have made their decision. It is useless to wait any longer. Suddenly, Father sees the door burst wide open. "Get up, now! Hurry! Today you will be set free!" He doesn't know whether to believe his ears. The other two hostages, filled with hope, have already scrambled to their feet. The three prisoners are led out into the open and begin walking, escorted by their kidnappers. Fr. Osnaghi feels light, as if a great weight has been lifted off of him. Soon he will be free again. But not very far from the hut, they stop in front of a large freshly dug pit, two meters deep.

At a signal from the chief of the brigands, they suddenly tied the hands and feet of the three prisoners; the young Huang began to shout and cry. Meanwhile, with a fierce kick they sent Fr. Osnaghi rolling into the pit; with a second kick they rolled in the cook (the catechist, according to other sources), who fell on top of Fr. Osnaghi, and they immediately began to cover the pit with earth. Huang San has repeatedly affirmed that Fr. Osnaghi, finding himself tied up at the front of the pit and seeing no means of escape, let forth with a loud wail, in which he shouted some foreign words and some words in Chinese, calling his mother. And while the brigands were burying the hostages, while the earth was piling up upon their bodies, Fr. Osnaghi and the catechist continued to cry out, until little by little, their cries ceased. (From the diary of Fr. G. Pollio)

Huang, the son of the mandarin, is released.

home