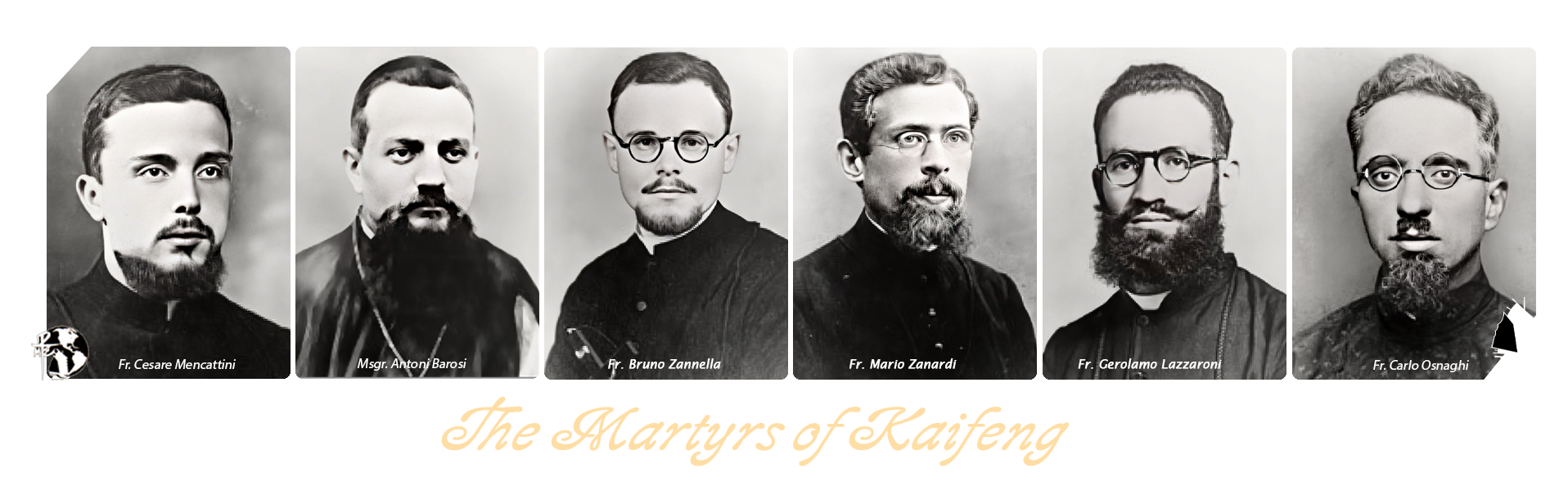

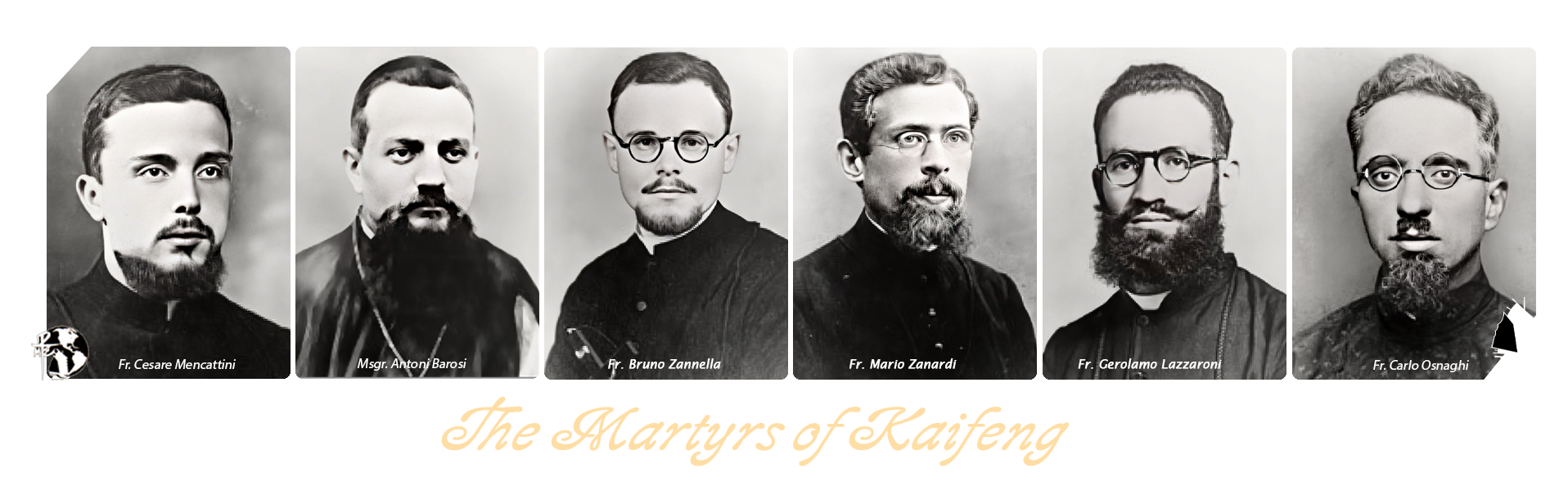

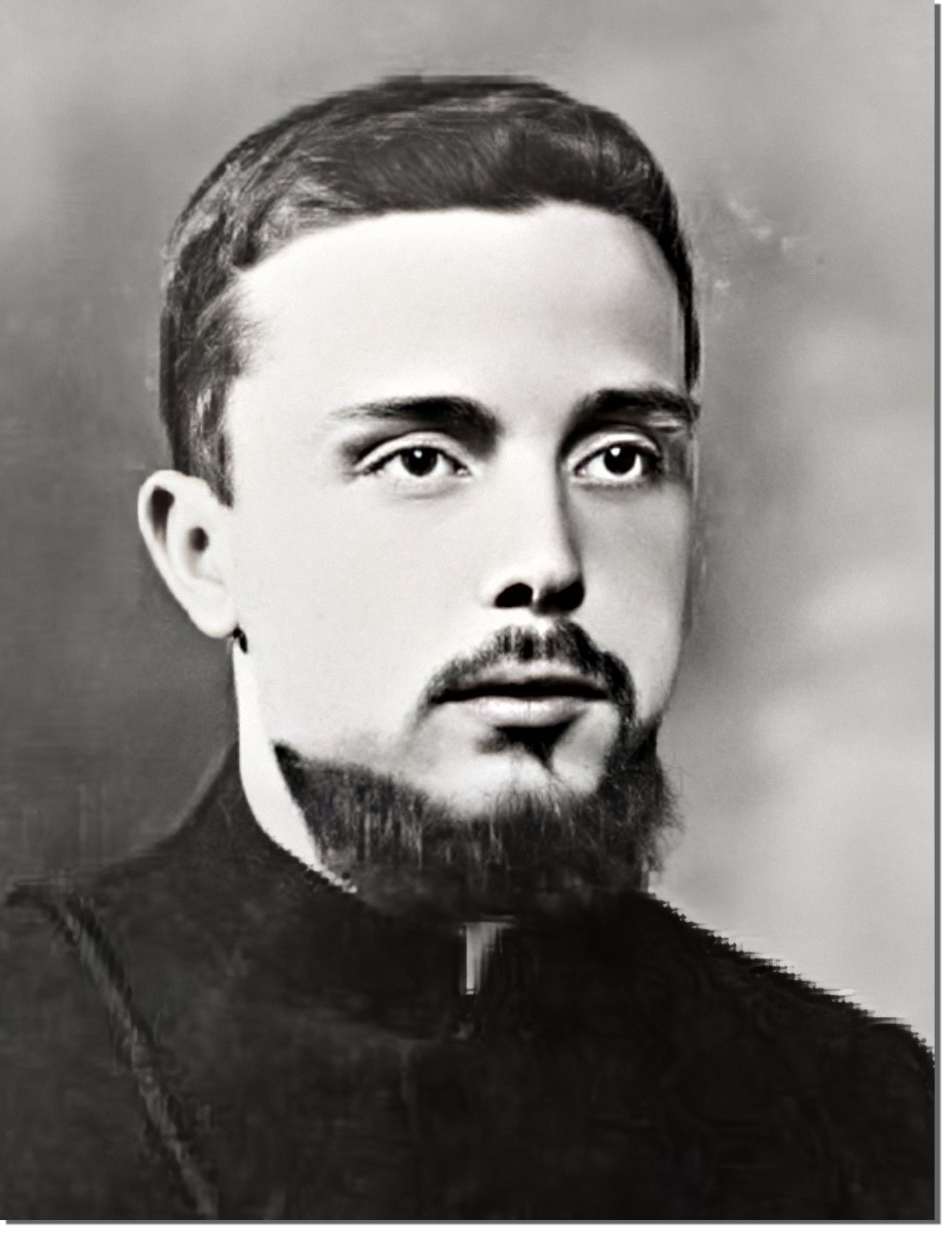

Father Cesare Mencattini

(May 7, 1910 - July 12, 1941)

September 17, 1927: the doorbell of the P.I.M.E. seminary at Agazzi, in the Arezzo province, rings loud and long. Looking out of the window, the rector sees a young man standing in front of the door, with sparkling eyes and a determined face:

"Will you take me? I want to be a missionary!"

He is from Bibbiena; he is seventeen years old and his name is Cesare Mencattini. It has been five years since he left home to attend, first the seminary of Arezzo, and then, due to delicate health, that of Cortona, where he completed his high-school studies with honors.

Now, however, the desire to be a good diocesan priest is not enough for him. The idea of the missions has been constantly growing in him, so much so that one thought has almost become a personal slogan:

"So many poor without Christ are waiting to hear the message of God."

The road ahead is still long, but his enthusiasm never wavers. He likes to study and does so with dedication, but whenever he can he spends some days in the nearby forest of Camaldoli, immersed in silence and in nature which enchants and uplifts him, reinvigorating him after months of being cooped up with his books.

His spirit is enraptured by the marvels of creation. During one trip, after a night spent with his friends counting the stars, he sees the top of Mount Pratomagno, on which a gigantic cross is mounted.

"That site," he would write years later,

"inspired in us a great desire to conquer that proud mountaintop. We walked the paths of the mountain chain which separates Valdarno from Casentino. A little before nine o'clock we crossed the beautiful grasslands that were like a velvet carpet ... Oh, the wonderful sights of that valley!"

His spirit is lifted up to God as he climbs Mt. Verna:

"We passed through Abetone and by the rock of Frate Lupo; from the terrace of the Penna we could never tire of admiring that enchanted Valle Santa! I could have stayed there for hours in meditation ... The vast horizons invite the soul to grow, they inspire great things, and we felt on top of the world ... There, from that mountaintop, St. Francis could very well have sung the Canticle of the Creatures ..."

Upon finishing theology studies at the P.I.M.E. seminary in Monza, he prepares for the priesthood:

"Let's not think that we can take any credit before God by becoming missionaries! We are always debtors to the Lord for this great grace which we will never understand while we are in this world." In Christmas greetings to his younger brother Pasquale, a seminarian in Cortona, he writes:

"Soon we will be priests, in keeping with the mystery of the feast we're celebrating now! Our priestly life will be a continual hymn of "Glory to God" and a constant message of "Peace to men ... " As much as you can imagine the sacrifices of our vocation, you will never be able to fully understand them. We have to be ready for anything ..."

His greatest ambition is to put into practice the example of Christ, but he is also aware of his own weakness and understands that to be prepared to take on such suffering, he needs to be well trained; and his "training" even includes undergoing a surgical operation, without anesthesia.

On September 22, 1934 Cesare is ordained a priest. During his brief stay with his family, he is already acting like a missionary, preaching retreats, visiting the sick in the hospital, and attending missionary meetings in Casentino.

On August 9, 1935, at the appropriate hour of sunset, in the faint light of the Institute's chapel, the Superior General greets the new missionaries with the words of Jesus to His apostles:

''I'm sending you like sheep among wolves ... " and speaks of the difficulty of their choice without hiding his fears and hopes.

Twelve years of formation, a vocation nurtured for so long a time, and now they were close to realizing their dream.

"I have a feeling," writes Fr. Cesare,

"that I will go to China, because that's where most of the assignments are destined this year. And this is really where I want to go, because it is currently the place where there is the greatest hope to crown our lives with the tiara of martyrdom." This thought accompanies Cesare and his companions as, from the train windows, they watch the figures of their families and friends at the Milan station recede in the distance. At that time, departures were characterized by a knot in the throat and a look in the eyes that said: We'll never see you again, except in heaven.

After a long sea voyage, Fr. Cesare arrives in Shanghai on September 10, 1935:

"I am so happy to arrive and to be able to give God this proof that I love Him, leaving behind the persons and things held most dear ... I am in my adopted country. I thank the Lord that He has brought me here among the Chinese. Now I must acclimate myself and die to my own way of living, in order to adopt a new one."

It's not easy. During the nine months of language study at the P.I.M.E. Regional House in Kaifeng, he can already recognize the difficulties a missionary must confront:

"Immense populations live here in desolation and misery in regions which extend for hundreds of kilometers. We missionaries could not reach everyone, even if we had wings. We're limited to doing very little in comparison with the immense work there is to accomplish. The inhabitants of these areas are reduced to the most extreme poverty, the results of brigands' passing, war, and the flooding of the Yellow River. Along the roads you see groups of vagabonds, who don't even have a hole in which to spend the night nor sufficient clothes to guard against the cold, which is so intense here in Henan.

You can't imagine what it's like for us missionaries to live here. Not only are there the physical sufferings, which are very real, but we also have the feeling of being alone in the midst of these people who regard us with indifference and disdain. We're often the object of insulting words. When they see us walking by, for example, they say, "Here comes a European dog." If only they knew how much good we wish them and the sacrifices we have made and are making in order to live in their midst!"

But Fr. Mencattini is not discouraged, because he knows that he remains in the hands of God, even in this

"desert of yellow sand, so small and fine that you find it settling in your eyes, your ears, everywhere ... In this unlimited lowland, where everything looks the same ... What a contrast to the enchanting green vistas of Casentino!"

Still, he is able to be happy. In fact, in June of 1936, when he is sent to the vast district of Huaxian as assistant to Fr. Paolo Giusti, he writes to his brother:

"I am happy to be a gypsy priest, without a church, without a rectory, without benefits, but rich in souls, lacking in clout but renewed by grace! My Christians are poor but truly good! They are so attentive when I speak of the goodness of God and eternal life! Then they all kneel on the bare earth, under the stars, to pray ... Tell me, if this is not true happiness! After having lived for six days in rat holes with beds of mud, this room of mine is worth more to me than the salon of His Majesty the King of Italy and the Emperor of Ethiopia. I assure you that I am truly happy, because I have a contented heart: content that I have left my loved ones in order to turn all of my affections toward God and toward the many poor people who are so dear to me now that they have been reborn in baptism; content that I traded the beauty of Italy for this desert of yellow sand which is becoming as familiar to me as my own village; content that I left behind my studies, to which I dedicated such effort, to become ignorant and to express the beauty of our religion in a language which is not my own, using only the most elementary terms and simplest comparisons; content to do without the grand liturgies of our Catholic countries in order to celebrate the Mass and administer the sacraments in rustic and poor chapels ..."

Thus Fr. Cesare throws himself into the "excursions" through the endless plains of the Yellow River.

Leaving his "headquarters" at Baliying every Monday morning, he goes by bicycle to visit the Christian villages, returning home each Saturday evening for Sunday Mass.

"My work consists not so much in increasing the number of Christians as in reorganizing the communities, making sure that each one has a mud chapel or at least a roof of straw under which to gather for prayer, training catechists to lead the people, establishing a fund in each village to cover the inevitable expenses ..."

Just as Fr. Cesare is beginning to see the first promising results of his pastoral plan, the Sino-Japanese war breaks out, and the future becomes increasingly dark. He has to suspend his plan to open schools, send the catechists home, and confront the most urgent needs of the people.

In 1937 the Japanese advance becomes ever more alarming: trenches and suspicions begin to appear.

The hostilities begin. By January of 1938 the war is raging, and in between brief periods of truce, there are fierce bombings:

"All of the authorities have disappeared. With the continual passage of soldiers, the food supply, already diminished by the damage done to the harvest by the floods, is almost gone. Looting and famine are inevitable." Fr. Cesare often moves up to the front lines to assist the wounded, comfort the dying, and bury the dead. He is often chased and captured by the troops of one party or another. Finally, in February of 1939, the Japanese establish a garrison in Huaxian to control the city and ransack the countryside.

"The Chinese, so lacking in arms and unable to resist the Japanese, who advance with cannons and automobiles, have adopted this defensive tactic: they destroy all the roads ... Thousands of people have been commandeered for this immense work; night and day for two months, they have dug deep pits in all the streets. The painful effort, which the people must put forth with no compensation, is more than you can imagine.

There is the added danger of being surprised by the Japanese. Even my bicycle paths have become difficult. On my last trip I had to pedal through the fields and cross from one pit to another with my bike on my back. They hope to make it impossible for the autos and armed carriers of the Japanese to pass through. Instead, the Japanese, even with ten cars and several large cannons, have easily reached this area and surrounded it. The current conditions for us missionaries are difficult. The Japanese have a garrison in the city; but outside, on the pretext of defending the country, great numbers of soldiers roam about, harassing the poor people so much that they are called "soldiers who eat everything." We are in the middle. We are doomed if we do not remain neutral! It would be impossible for us to stay.

The places once occupied by the Japanese and often abandoned because of their poor condition, fall into the hands of the communists or other soldiers, or brigands. The city of Huaxian has suffered this fate five times in one year: occupied by regular troops, the Japanese, brigands, the communists, and now once again the Japanese, who are quickly working to rebuild it.

What ruin! The destruction caused by passing soldiers is worse than that caused by cannons or bombs dropped from airplanes. After a voluntary retreat of the Japanese, when the Chinese take over the city again, everything is destroyed. Railway stations, city walls, everything must be reduced to heaps of rubble.

For more than a year there has been no commerce, no schools, no authority - only disorder and confusion which seem to have no end in sight."

The war seems like it will go on forever.

At the beginning of 1941, describing the chaotic situation in which he still finds himself, Fr. Cesare writes:

"I've been wanting to write to you for some time, but the conditions here have prevented me. I wish I could describe to you the world in which we live! You would wonder how it is that no missionary has been killed so far in Weihui. I will try to tell you something. For four years I have been in charge of the same district, and I have not had one day of peace. The war is always here.

My entire area has been and is always full of soldiers, who cause quite a few troubles for us. What a strange war! The front is everywhere. It's impossible to understand anything amid this disorder. I can't find the words to give you an idea of it. There are the communists. They work through fear, always moving about and operating in the night. It will be bad for us if they are able to establish themselves here. I have met up with them four or five times. Truly, I was only saved by the protection of the Lord. The first time, they fired three shots at me, but were not able to hit me, nor the servant with me, although the bullets whizzed by our heads and backs. The second time they took away my chalice and pyx, and tore up my missal. A third time, at night while I was returning from giving last rites, they stopped me at rifle point. A few days ago they tried to take me with them, but they soon released me, without even searching me. Luckily, they cannot stay in one place very long. They are constantly under the attack of the Japanese and the soldiers of the old government.

Then there are also the soldiers of the new government. You can add, finally, a multitude of brigands, who try to bite off more than they can chew, committing all sorts of crimes and robberies. Among their victims are two catechists who were taken away: one was buried alive and the other was decapitated.

Imagine the confusion with all the different types of guerrillas! I am always in the middle. It's been going on for more than three and a half years, and who knows when it will end?

One day we're under one group, the next day another. Always thinking of the best way to get along with all of them, I try to continue my work. As you can see, I'm in a difficult and dangerous position. In these past months, almost every day you can see villages in flames, while rifle volleys are heard almost constantly. And we stay here, waiting for it to pass.

Just now as I am writing this, not far away I can hear gunshots, and the crackle of machine-gun fire. Maybe it is the brigands attacking a village; maybe it is the communists battling with the soldiers of the new government. As soon as night falls, I can be sure to hear the rumble of the cannon, with which the Japanese, for the moment, are routing these scraggly soldiers.

In spite of such chaos, I have been able to build a small chapel. It is a luxury in these parts, where there is not a more beautiful structure. The walls are made of mud, covered by bricks on the outside. I have in mind to decorate the unadorned walls and to build a decent altar to replace the wobbly table we now use.

I also want to build a dryer, healthier house for myself. The wood is ready. Then the hall for teaching catechumens, the school ... What dreams!

If only the war would end! That is my dream, my greatest hope. I'm so tired of this chaotic life, and so sick of seeing such misery and broken bodies. I don't know how much more I can take, feeling the tears and groans of so many.

In our vicariate, many missionaries are failing in health. But I can still be counted among the healthy ones."

Even though he knows that the situation is getting more and more dangerous and could explode at any moment, Fr. Mencattini decides to stay at his post. Indeed, back in July of 1939 he has written:

"Many times I get on my knees expecting to die. But I have never left my post. If I have to lose my life for the sake of my ministry, I will be truly happy."

In 1940 they decide to stay on as well even though cholera strikes. The workload is great; Fr. Cesare comes down with virulent dysentery; Fr. Giusti has malaria. And even the bishop calls them back. Still they stay on.

"The opportunities for doing good are so great here! Many of the poor have no one else to help them ... We have no fear of death here. We would really be leaving nothing behind in this poor world. All of our strength, energy and health must be dedicated to the Chinese, until we can do no more."

They have to go to the farthest reaches of the district to console the people, help hundreds and hundreds of refugees and sick, bury the dead. The bishop is forced to give in to their determination.

Then; suddenly, a telegram arrives in Italy, addressed to the Superior General of P.LM.E.:

"On July 12, 1941, Fr. Cesare Mencattini fell victim to an assault by a straggling band of Chinese soldiers. In the same incident Frs. Angelo Bagnoli and Leo Cavallini were wounded." The telegram gives no details, and the superior must wait until November to find out the particulars. The facts are finally reconstructed in a letter from Fr. Sordo, the procurator in the Hong Kong mission.

On the evening of July 11, after an exhausting journey on bicycle under the searing sun, Fr. Cesare arrives in Huaxian from Baliying. He has come to meet Fr. Giusti and the two of them plan to negotiate the purchase of some land in order to build a school for girls. They decide to speak to the bishop. The next day, Fr. Cesare plans to go to Weihui in the company of Frs. Bagnoli and Cavallini.

Thus, after the dawn celebration of the Mass on July 12, the three depart. Fr. Cesare is on his bicycle, being towed by the motorcycle ridden by the other two. Around nine o'clock the small band reaches the market of Qimen. Everything seems quiet; no one could foresee that at the same time some irregular soldiers, said to be connected with the mandarin of Rencun, would arrive. The fathers, just a few hundred meters from the entrance of the market are shot without warning by these soldiers, who have hidden themselves behind a small wall surrounding the market. All three are hit by the dum-dum bullets. Fr. Mencattini falls to the ground with a painful cry, his stomach ripped open by the bullets. They finish him off immediately with a bayonet and after stealing everything, including his clothes, they bury him.

Fr. Bagnoli, wounded in the left leg, has just enough time to call out his name and give him absolution. Fr. Cavallini, hit in the left foot, has a fractured ankle and falls with the motorcycle into a ditch on the side of the road. Fr. Bagnoli tries desperately to stop the brigands, explaining that they are Catholic missionaries, but they only reply,

"We know." Then they get a cart and carry the two wounded fathers into the market. They put them under a pagoda where they remain until four o'clock in the afternoon. Anyone who tries to come close or to help them is threatened.

The two survivors are condemned to be buried alive, but providentially an influential Christian official who has heard of the events arrives on the scene. After hours of discussion he is able to free them from the hands of their assailants. Then, in two barrows pushed by hand, Frs. Bagnoli and Cavallini are transported to the hospital in Weihui, about 25 kilometers away, where they are finally able to receive treatment for their wounds.

The body of Fr. Mencattini is disinterred, again through the intervention of the Christian official and placed in a wagon. The next day it is transported to Weihui, where his confreres, the faithful, and also many non-Christians gather to wish him a last farewell.

home