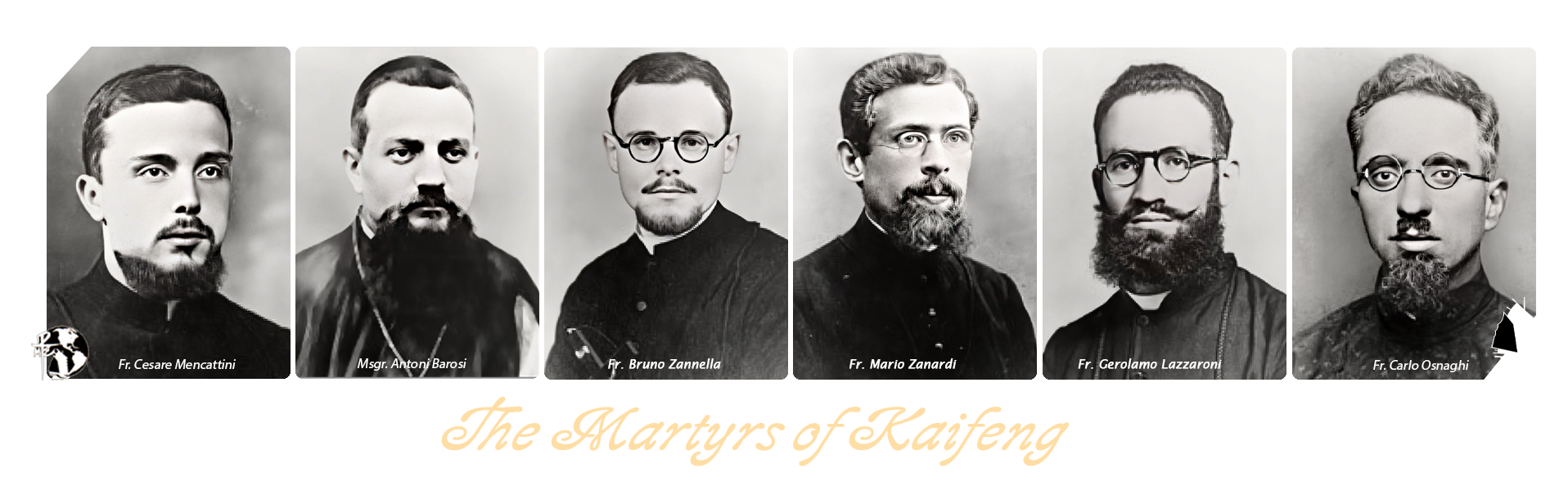

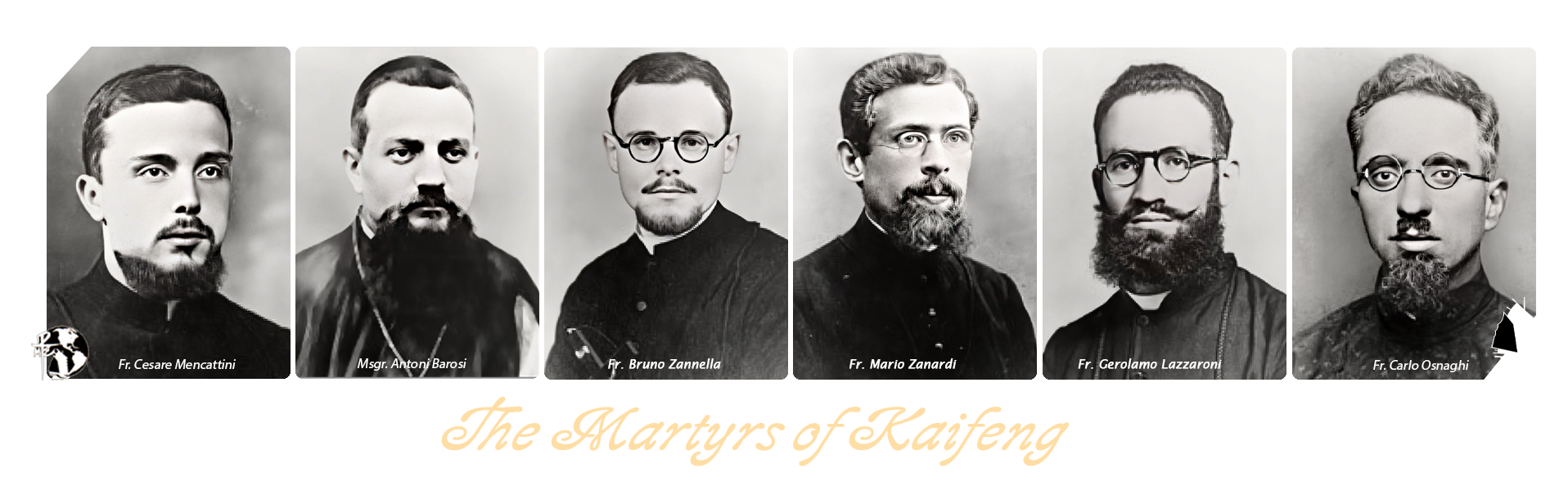

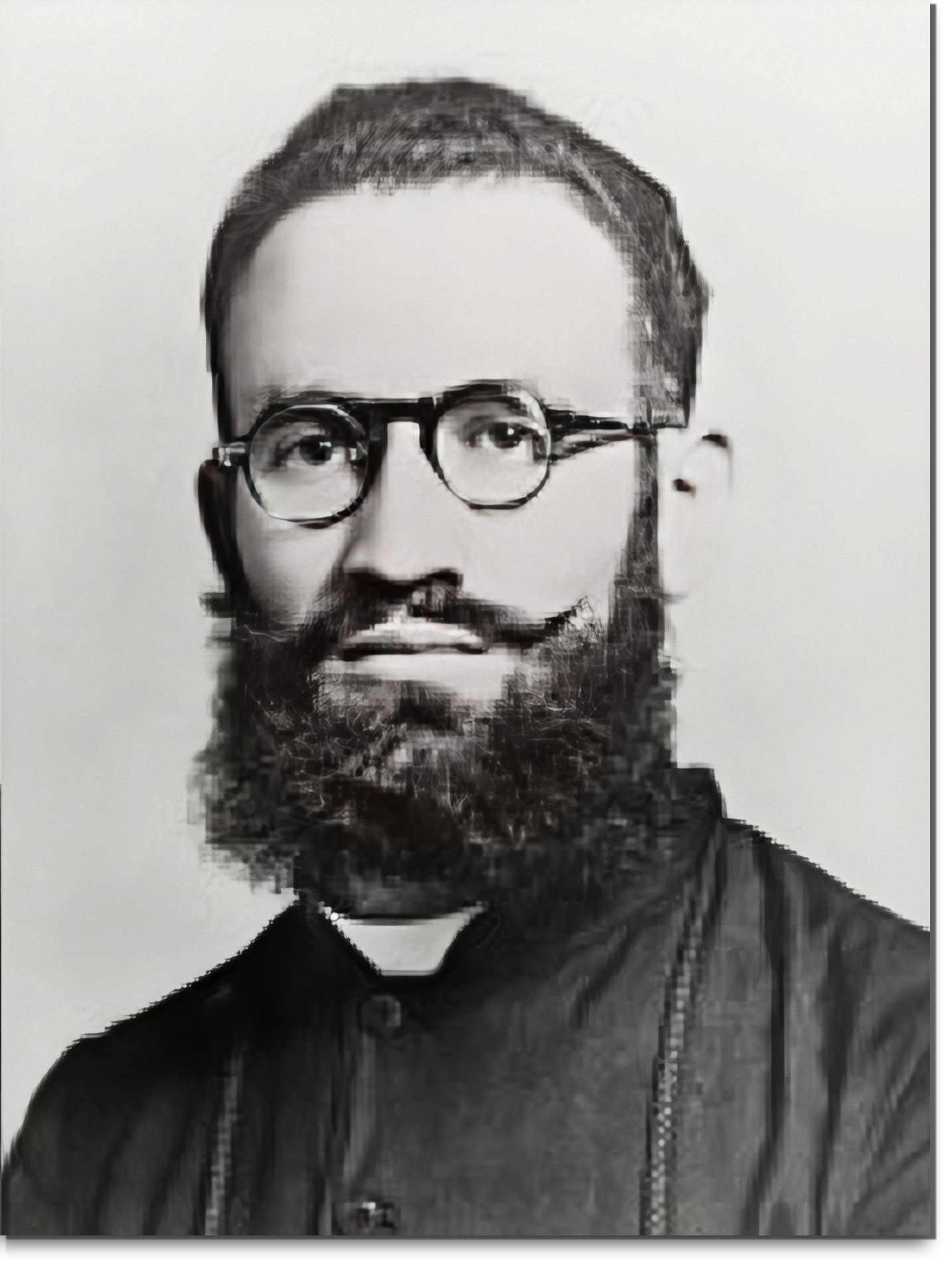

Father Gerolamo Lazzaroni

(SEPTEMBER 27, 1914 - NOVEMBER 19, 1941)

Colere: a tiny village in the province of Bergamo, located in the enchanting Valley of Scalve, on the north slope of the Presolana Mountains.

It is early 1900. The families of this area, in order to survive, cultivate some vegetable gardens, grow a little hay, and rent one or two cows in the wintertime so that they can be sure of a little milk in the long, cold season. Often, however, it is not enough, and the head of the family must go elsewhere in search of work.

Such is the life of the Lazzaroni family. Gerolamo, from an early age, helps to collect the potatoes, cut and bale the hay, and herd the sheep to pasture. With his three older brothers, he has to help his mother keep the family going, because his father leaves for long periods of time to find work as a miner in Australia.

Thus, when Gerolamo confides to his mother his desire to enter the seminary, it is inevitable that the response will be a terse no. Really, it would be unthinkable; just the cost of his travel to the city of Bergamo is more than the family budget can handle. It's best if he simply puts this dream aside. There is no way the poor Lazzaroni family can pay for his room and board nor the required uniform (accustomed as he was to wearing patched pants and sandals). His mother hopes that this is just a passing phase.

But in 1927, after the return of his father for good, Gerolamo (now 13 years old) brings up the topic again. The presence of his father assures some stability for the family, and the savings brought from Australia can provide a significant, if limited, respite from financial worries. Thus, in November of 1927, with a third-grade education and a little bit of Latin picked up from his pastor, Gerolamo leaves Colere for the diocesan seminary of Bergamo.

Used to long walks in the mountains, always out in the fresh air, at first he finds seminary life difficult. Those long hours sitting at his desk and listening to things which are incomprehensible to him sometimes seem like a prison sentence. He can't sing to the squirrels as he used to do while collecting wood with his brothers. He has to stay closed up in a classroom, while the sky is blue and he feels like running outside, with the breeze flowing through his hair, climbing mountains, scrambling to the top of Presolana.

With all the difficulties of studies and community life, he feels like giving up and going home. But his vocation cannot be burst like a soap bubble; he trusts in the Lord and often remembers the words of his pastor: "Nothing good can be accomplished in life without effort and sacrifice." With his head in his hands, then, he returns to his books, sure that even now he is already in God's service.

Eventually, the environment and people, so different from his own culture, begin to become familiar. He is assigned to lead treks through the mountains, to organize soccer games, and to fill the evenings with activities designed to overcome homesickness. Lively and humorous, he invigorates the seminary with his wit. He also progresses in his studies, so much so that when classmates do not understand some topic, they come to him for an explanation.

In the meantime, during his high-school years, his desire to be a missionary grows, and in 1935 he transfers to the P.LM.E. seminary in Genoa, and then on to Milan. A few months before his priestly ordination in 1938, both of his parents die within a short time of each other. It is a heavy blow for him, since he is so attached to his family, but even in this difficult situation, he trusts completely in the Lord. To those who offer condolences, he replies: "The Lord has already granted them their reward for the sacrifice of offering their son to Him for the missions."

Ordained on September 24, 1938 in the Milan Cathedral, he celebrates his first Mass in Colere. At sunset, his friends give him a great surprise. In the valley, lights begin to flicker and soon take the shape of an enormous chalice and host.

At the age of 24, he is informed of his destination: together with his classmate Valentino Corti he is assigned to the mission of Hanzhong in the Chinese province of Shaanxi, the most distant of the missions of P.I.M.E. And so, on August 16, 1939, he leaves Genoa for a destination that he will never reach because of the Sino-Japanese war.

After disembarking at Shanghai, he reaches Kaifeng and stays there with the other new missionaries for a year of language study. His joviality and love for jokes do not diminish a bit: "My professor is a good Catholic. Too bad he can only speak Chinese! To help us understand his baffling sayings, he moves right and left, he sits on the ground or climbs up on a chair, he acts blind, he jumps and dances; it's all quite entertaining." To break the monotony of studies, the fathers sometimes make little trips outside of the city, visiting one Christian community or another. The elusive language remains a torture for Fr. Gerolamo, even though he is beginning to enjoy its beauty. When he listens to a Chinese telling a story, he pays more attention to the way of speaking than to the content, marveling at the ease with which every detail and shade of meaning is expressed. Soon he will try to preach, and will then be a "true" missionary. This is his great desire, as he expresses in a letter to his sister:

"Pray that I learn this language as well as possible so that I can do much good here, where the Lord wants me to be. Every day I become more aware of how unprepared I am for the mission entrusted to me by the Lord. It is not beautiful homilies that convert souls, but rather all the daily sacrifices that Providence places before us."

In June of 1940 the year of language study is over, and all the missionaries leave the regional house for their respective missions. But Frs. Lazzaroni and Valentino Corti, assigned to the vicariate of Hanzhong (Shaanxi), cannot leave. The long trip is dangerous even under normal conditions; now, because of the Sino-Japanese war, it is practically impossible. Fr. Gerolamo must wait. But he feels like a fish out of water.

"I am well here, and far away from any danger, but I am not at my post. I want so much to set out for my mission, far away and isolated, toward the border of Tibet, where you can find the true and authentic China of Confucius ... I continue to hope that a way is opened to Hanzhong. Ah, if only I could go by bicycle!"

The enthusiasm of youth is not diminished by the prospects of the risks to be faced, so much so that if it were up to him, he would leave for his mission by any means of transportation.

Unfortunately, though, he is not able to do so, and while waiting for better times, he stays in Kaifeng. Finally, he is assigned to the mission of Dingcunji, of which Fr. Bruno Zanello has just been named pastor. The two of them leave the city together.

After going a short way by train, no one knows how the journey can continue. There are no roads anymore, only flooded areas crossed by raft to avoid the slimy, muddy ground. Having conquered the 300 kilometers to Dingcunji, Fr. Gerolamo writes:

"I traveled by train, by bicycle, on foot, by boat, and by ox cart. But 1 have finally arrived where the Lord wants me to be!"

Fr. Edoardo Piccinini, the former pastor of the district, now assigned to Taikang, is there to meet them and to give his successors all the necessary information about the area. Thus, just two days after arriving, the three missionaries are on the road again, to visit the different Christian communities. Even though he is in the midst of much desolation because of the flooding, the brigands, and the war, Fr. Gerolamo is happy to be living the dream held so dear during his years of study and prayer.

Back in Dingcunji, Fr. Lazzaroni is given the job of teaching catechism to the children every day, during the last hour of school.

Gerolamo likes the Chinese children. It hasn't been that long since his own childhood, and he understands very well what it is like to be without adequate shoes in the winter, or to walk in a rainstorm without an umbrella, or to be unable to replace a notebook which is filled up. He loves these children, understands them, and is ready to give his life for them.

He writes on January 2, 1941:

"I spent Christmas here at Dingcunji, while Fr. Bruno was about 30 kilometers away. More than 200 Christians came for the celebration, and all of them wanted the sacrament of confession; then they participated in midnight Mass ... I was dead tired when I walked out of the church at noon, and there were even more people waiting. All of them stopped by the mission house to give their Christmas greetings and to bring me a gift: a bag of sweets, a chicken, a dozen eggs, a homemade cake ... and to think that they have barely enough to keep from starving! Certainly if I did not accept, they would be offended. I redistributed everything to the children ... So, in general, I'm doing well here. I miss news of the Western world, but the next time I go to Kaifeng (300 kilometers away), I will bring my radio, and then things will be even better!"

He is content with little and still knows how to be humorous. In a letter to his brother-in-law he writes:

"My beard is not growing very well, because I don't have anyone to pull on it. Occasionally I try to pull on my pastor's beard, but he is too good to respond in kind." And he adds:

"I know that you are a good bricklayer, but did you know that I am a good road builder? If you want to go to Heaven, you have to build the road yourself."

This has more than symbolic meaning for him; he really does have to repair the roads on many occasions. He writes in March of 1941:

"Last week I redid part of the road which I had just repaired five months ago, when I got here. Then it was nothing more than an extension of the Yellow River; now it is passable for a few kilometers, but the rest cannot be fixed."

Meanwhile, the suffering increases.

"I am very happy with my Christians, and I feel so sorry for their misery," he writes in the same letter.

"In autumn, they planted some corn. But now in the spring, with the melting snow, the river has overflowed causing immense damage. Except for some rare exceptions, they live in miserable, dark, smoky hovels, open to the four winds, which blow strongly on some nights. Food is scarce and miserable. Now that the Japanese have taken away the rice, there is not even that. The poorest in Europe are richer than these Chinese."

He suffers with the people and for the people.

"This is a real no man's- land. As if all the rest weren't enough, there are the Japanese troops, the Chinese soldiers, and the brigands dressed in camouflage. All of them do nothing but harass the people."

The camouflaged brigands - these are the real rulers of the territory. They make themselves at home, and no one tries to get rid of them. It is easier to ignore the problem and to pretend that it doesn't exist. The district of Dingcunji is on the border of three provinces, each of which passes the responsibility to the other, claiming that the area is not under its authority. Thus, it is here that all the outlaws congregate: deserters, mercenaries, common criminals, all gathered in unruly, undisciplined groups, pushed toward violence by hunger and unrest. In a word, they are men to fear. Still, despite this situation of extreme insecurity, the missionaries remain and travel here and there amidst the danger, in solidarity with their people.

Fr. Gerolamo is not afraid of the difficulty, the struggles, and the dangerous trips: he is strong, courageous, and not the type of person to suffer oppression passively. Yet even the strongest must sometimes give in to the events surrounding them and to the prudence of "weakness."

On November 18, Fr. Lazzaroni is alone at Dingcunjji. Fr. Zanella has gone to meet the bishop. In the little community, everything is prepared. A rainbow at the entrance of the village is a sign of hope.

home